[ad_1]

“They argued, with considerable evidence, for the healing power of sun and air for the body and mind,” explains Dr. Annebella Pollen about some of the Nudist Clubs featured in her book Nudism in a Cold Climate. “Members found the practice liberating and enjoyable.” Dr. Pollen focuses the book on the history of nudism in Britain. In the 1930s, it’s was a huge movement with photographers looking to get in on it. Some found that it was also quite a profitable venture for them. We’ve featured tons of stories on sub-cultures around the world, but this one is incredibly fascinating. So we spoke more with Dr. Pollen about the photos and the movement. Nudism in a Cold Climate is available for purchase on Amazon or from Atelier if you’re interested.

“With a careful selecting hand, I showed how nudism included nude men, women and children. I also looked for what early nudism excluded and images that aroused controversy in the magazine. Black and brown bodies were often marginalised and spoken about in objectifying terms. Early nudism in Britain had particular ideas about tanning that always assumed white skin.”

Phoblographer: You worked on sourcing the images. To you, how does the work of each contributing photographer distinguish themselves? What did each do that made their work stand out from the rest? Some of them seem to be more about documenting things while others have an emphasis on posed portraiture.

Dr. Annebella Pollen: The focus of the book is on the history of nudism in Britain from its formal beginnings in the 1920s through to a period of dramatic fracture in the late 1960s / early 1970s. I especially focus on the role that nude photographs played in the depiction of the movement in a period where nude images were not commonly available to see or to buy and when they were subject to strict obscenity laws. Nudist publications were a rare place where nude photographs could circulate publicly, with legitimacy (other locations were art and anthropology).

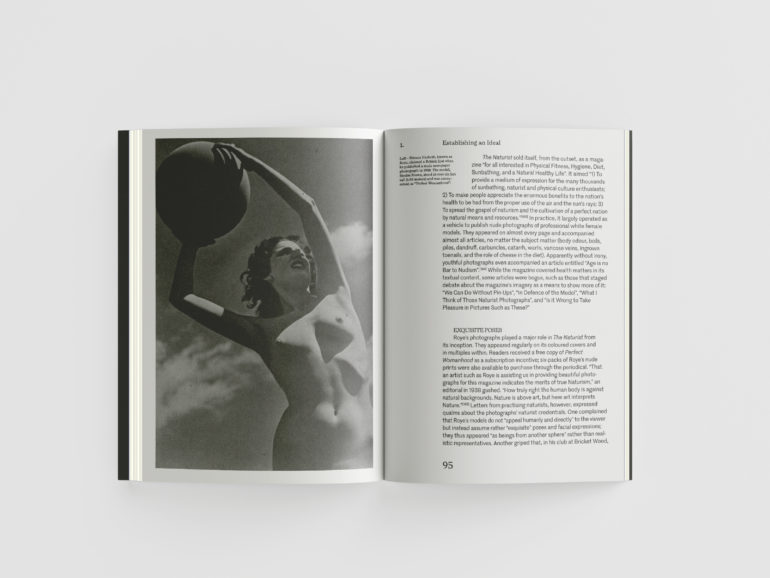

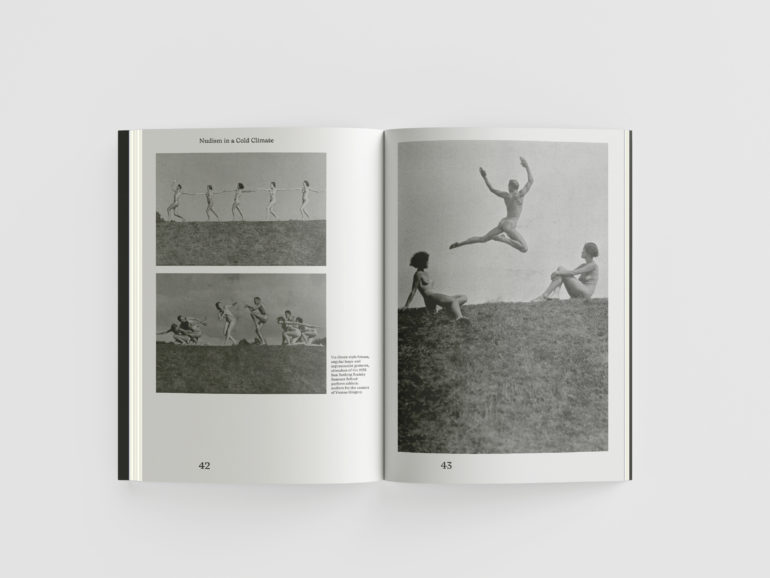

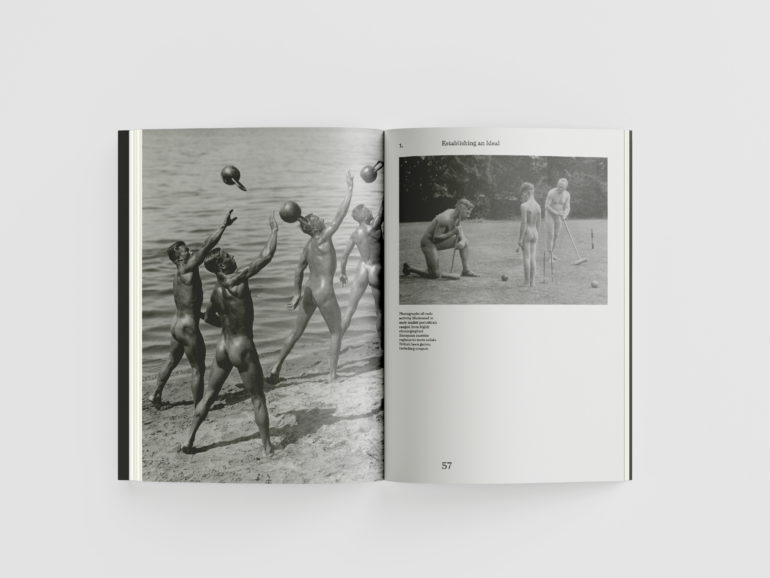

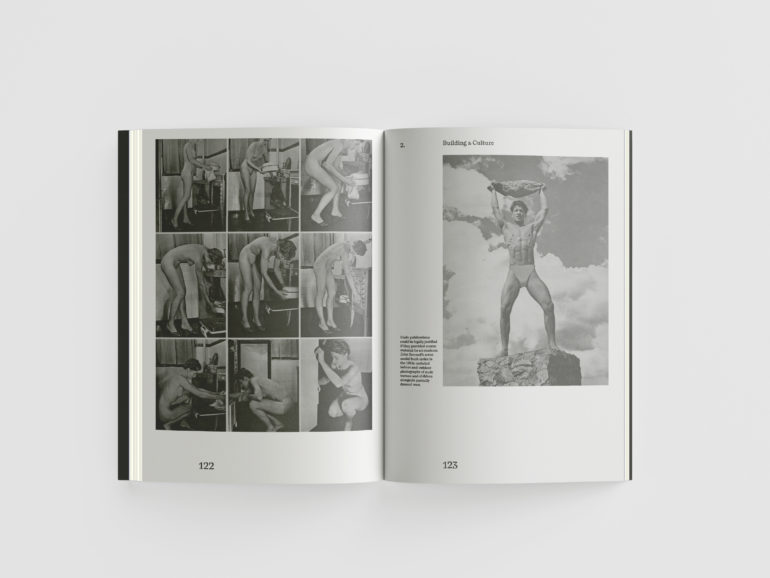

British nudist publications emerged in force from the 1930s. Their illustrations range from photographs of nudists going about their daily activities in camp – often depicting exercise and athleticism, as the movement was based on health ideals – to stylised and posed photographs that can be quite classical and painterly in artistic style.

Some photographs appeared in nudist books and magazines without credit, and some credited photographers took photographs for nudist magazines alongside other photographic work. Bertram Park, for example, who sometimes worked with his wife Yvonne Gregory, was a very prominent photographer of nudist nudes in the 1930s, but he was also a studio photographer of royal portraits. Edith Tudor Hart was another regular photographer for nudist magazines in the 1930s and 1940s but she is better known now for her documentary depictions of working-class life in London (and for recruiting the Cambridge ring of spies).

“Sometimes models were used to show bodies for nudists to aspire to.”

Some nudist photographers launched their careers during and after the Second World War producing nude work very close to pin-ups photographs, often with erotic intentions that were disguised by their nudist locations. This was the case with George Harrison Marks, for example, who later produced pornographic photographs and film. In other cases, models went around the other side of the camera, such as the photographer Eva Grant.

In many cases, photographers’ styles can be quite similar as, until around 1970, British law dictated that no genitals or pubic hair could be visible. There’s also a dominant emphasis on the bodies of young, slim, white women as subjects often posed in outdoor settings. Nudists argued strongly that their nude practices were for health reasons and had nothing to do with sex; photographs had to be chaste to emphasise this point.

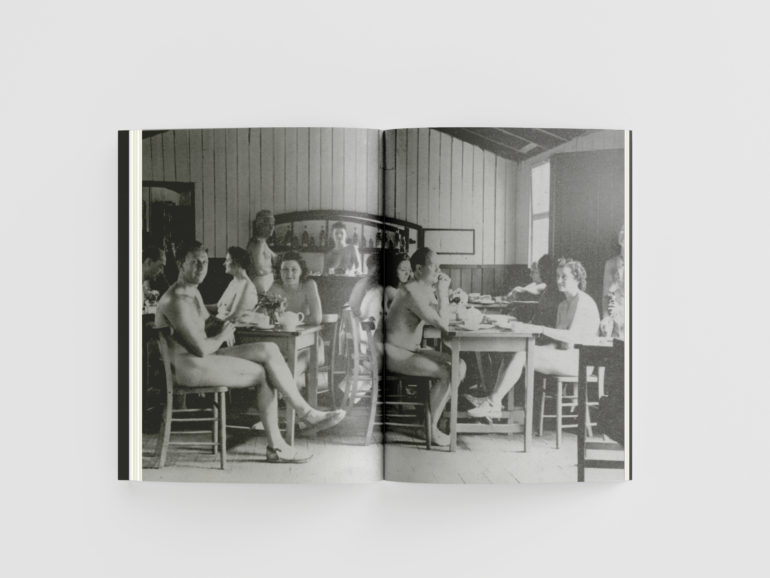

Sometimes models were used to show bodies for nudists to aspire to. Candid photographs of actual nudists in camps were also included in nudist publications but these were harder to make elegant and heroic as nudist bodies were inevitably all shapes, sizes, and ages, and nudist camp activities were sometimes mundane (such as digging latrines).

Phoblographer: What were these photographers’ fascination with nudist colonies? Was it a big trend back in the day?

Dr. Annebella Pollen: The movement started in the 1920s in Britain in a very small way. By the 1930s numbers were expanding, leading to a peak of 40,000 nudists just before the Second World War. By then there were also hundreds of nudist clubs (this was the preferred name, rather than colonies, which implied that nudism was a sect or a cult). There was also a 1930s boom in publishing books and magazines about nudism, which had huge circulation figures – over 100,000 readers a month. The abundance of nude photographs of models in these publications also helped sales among readers who were not nudists.

Some of the photographers were nudists but other photographers saw that serious money could be made by producing photographs for this market and began to specialise in outdoor nudes. One photographer of this kind was Horace Narbeth, professionally known as Roye, who produced books of nude photographs in outdoor settings that weren’t actually of nudists or even taken in nudist camps but, by virtue of being of nude bodies taken outdoors, they could still function as nudist illustrations. Roye wasn’t a nudist but he argued for more relaxed attitudes to bodies, but mostly to enable viewers the right to see more flesh without guilt and shame. He also took more obviously erotic photographs, which he published in other locations. Together, his books sold more than two million copies by the 1950s.

Phoblographer: When you were sourcing and editing the selections for this book, what made certain images stand out more than others?

Dr. Annebella Pollen: I reviewed hundreds of books and magazines and visited many public archives and private collections. I looked for images that showed a cross-section of what was typical – such as gymnastic poses and painterly styles in the more artistically-inclined photographs, and for photographs that showed ordinary nudist bodies engaged in camp activities. With a careful selecting hand, I showed how nudism included nude men, women, and children. I also looked for what early nudism excluded and images that aroused controversy in the magazine. Black and brown bodies were often marginalised and spoken about in objectifying terms. Early nudism in Britain had particular ideas about tanning that always assumed white skin. There was also worry about sex and sexuality. Nudists were concerned about publishing images that might prove erotically stimulating, such as homoerotic photographs of young muscular men in statuesque poses. I also tried to show the reality of the movement in the older and larger bodies of nudists. I also illustrated the book with images that were in dispute, such as the photographs of the late 1950s and 1960s which attempted to show pubic hair and for which photographers such as Roye and Jean Straker were taken to court.

“Some of the photographers were nudists but other photographers saw that serious money could be made by producing photographs for this market and began to specialise in outdoor nudes.”

Phoblographer: Why do you think people wanted to parade around nude? Do you see any parallels to today’s nudist camps?

Dr. Annebella Pollen: Going naked publicly and socially in 1920s Britain was viewed with great suspicion so the nudists who pioneered the British movement argued that the country was living under conditions of shame that they wanted to cast off. Some of British nudism’s founders were psychiatrists and physicians. They argued, with considerable evidence, for the healing power of sun and air for the body and mind. Members found the practice liberating and enjoyable. In the early days, camps were intellectual spaces of discussion as well as leisure so members gathered to enjoy vegetarian food and share interests in natural health with like-minded individuals.

There is a lot of continuity with nudist practices today, although now nudists prefer to be known as naturists. Its popularity may have diminished in some ways – there are around 8000 members of the main membership organisation, British Naturism – but at the same time, nudity in public has become more accepted, at least in some ways. Nudist beaches in Britain, for example, were formally instituted by some local councils in the 1970s, and images of nude bodies in print and on-screen are much more widely available. Some of the early British nudist camps are still going, but other people who might not call themselves nudist or naturist are happy to go skinny dipping or hang out in a hot tub with friends.

Phoblographer: You say nudists appear in tons of magazines and publications back then. What made it stop and disappear?

Dr. Annebella Pollen: In the 1930s, nudist magazines were one of the few places where nude photographs could be bought for just a few pennies over the counter. During the Second World War, new publications emerged selling pictures of pin-ups, and these achieved mass popularity in the post-war years when there was a boom in cheap pictorial magazines. These were rivals in some ways to nudist publications, at least for readers who wanted enjoy the pleasures of looking at nude bodies and didn’t have any interest in nudist philosophy.

By the later 1950s, some of these pin-up or ‘glamour photography’ magazines were quite racy, with sexualised images of women in stockings and underwear, for example. Many had to still disguise their intentions to remain in legal circulation, however, so some claimed to offer instruction for artists who wished to draw from a model, for example.

Commercial nudist magazines continued into the 1950s and 1960s but found themselves mixed up with wider cultures of sexualised nudity and some members were very unhappy about it. Others embraced new attitudes to sexual liberation and made their images more sexually suggestive. This led to some fundamental splits in the movement by the end of the 1960s, when titillating publications such as Penthouse began to dominate the market for nude photographs, and naked and partially dressed women’s bodies could be seen in all kinds of publications including national newspapers.

Naturists – those who believed strongly in the health practices of their movement – created their own private circulation publications to separate themselves from these sexualised cultures. Naturist magazines still exist today – some of the original ones are still going – but they mostly serve the interests of their members, and their circulation numbers are small. Those who once bought nudist magazines to view naked flesh now have ample opportunities to find images elsewhere.

Phoblographer: Were any of these photographers actually a part of the nudist clubs at all or were they just observers? Do you feel that any of this may have influenced the way they worked?

Dr. Annebella Pollen: Yes, there were nudists who were photographers and some were highly accomplished, with Royal Photographic Society letters after their name, such as Anthony Peacock and Colin Clark. A Royal Photographic Society photographer, writing in the 1950s, noted that the most authentic images should be “of the nude, by the nude, in the nude, for the nude”, and some practitioners put this into practice. It helped them understand nudist communities and they represented members as they wished to be seen – not sensationalised or sexualised, but as a legitimate social movement.

Words by Dr. Annebella Pollen. Nudism in a Cold Climate is available for purchase on Amazon or from Atelier if you’re interested. All images used with permission.

[ad_2]