[ad_1]

“The main difference between wildlife and sports photography is that in sports photography, the subject you’re trying to capture won’t try to eat you,” said a friend of a friend who will remain unnamed. Something said in jest, of course, but the fact is that extra precautions need to be taken when out in the wild photographing animals. Despite taking these, sometimes photographers can be on the receiving end of some unexpectedly scary moments.

All images in this article are used with permission from their owners.

At the onset, let me say that this article isn’t meant to portray wild animals negatively. If anything, it’s meant to be quite the opposite. A prominent wildlife photographer responded to my request for an interview on this topic by saying that it might portray animals in a bad light, as animals are only defending themselves when needed. Even as someone who hasn’t done any serious wildlife photography, I agree with him on the latter half of that statement. Armed with super-telephoto lenses, wildlife photographers often have to be well inside the familiar environment of a wild animal to get some good stills of them. And sometimes, when these animals feel threatened, even the more docile among them can turn hostile.

Animals Can Be Quicker Than You Realize

Akhil Vinayak Menon is a technologist by profession and a nature and wildlife photographer by passion. He’s been pursuing wildlife photography for over eight years. A trip to the Jim Corbett National Park in Uttarakhand, India, is where he encountered a scary moment. Here’s his story:

“For a couple of days, I and the guide/driver had been following a trio of elephants, possibly siblings. I managed to make some fantastic frames with the elephants, especially in the morning and evening light.

In this image, the beautiful backlight, the dense forests behind the elephants, and the elephants perfectly balanced in the frame makes this image special and unique. It is a beautiful habitat shot of the elephants in the park as well. The trio was very active, and this encouraged me to follow them through multiple days to get more shots around the park.

On the third day of safari, during the evening safari session, as a routine, we rushed back to the same area where we had been capturing images of the elephants. The path to the riverbed was narrow and had bushes on both sides of the road. As soon as we took a curve on the road, the trio all of a sudden appeared to the right of the safari vehicle, and the driver instinctively stopped the vehicle. These safari vehicles are specially made open jeeps with no roofing in order to aid undisturbed photography. So we were literally in the open and just a few meters away from the animals.

One of the elephants was taking a mud bath while the little one was grazing. The third elephant, however, seemed alarmed by our unexpected presence and our closeness to the gang. You can see him watching us. He observed us for a few minutes and appeared to settle down. We were quite close to the three elephants, and there were not much frames to be made at such close proximity. I quietly murmured to the driver to move further away, and then within a fraction of a second, the elephant that was watching us started to charge us.

All wild animals have their own way of conveying discomfort; now, elephants usually make sounds or at least mock charge. A mock charge is when an elephant charges towards you while making sounds and then stops at a distance from the intruder. I have had the experience of elephants making a mock charge at the safari vehicle in the past, so we anticipated that he would stop. However, in this case, the elephant did not stop, and for a moment, I felt that perhaps I was in for some big trouble.

Although a bit late, instinctively, my driver managed to put the vehicle in reverse as this was the only option and drive backwards; however, the elephant managed to get very close. It is indescribable the emotions that ran through my mind. My heart was pounding all the while, I had lost balance and dropped back on my seat hard, and my arms were hurting from the fall. Since the vehicle was being driven backwards, the ride was disoriented, and we ran over rocks and pebbles hard, all the more, making the experience unpleasant. The elephant had chased us for a good 50-70 meters before losing interest. We stopped the vehicle briefly with a sigh of relief.

Elephants, in general, are much more notorious than some apex predators such as Tigers in the Indian Forests. So our panic during the incident was valid. The one thing that we learn from such an incident is that it is always best to keep a safe distance from wild animals and to respond to their warnings promptly, especially the likes of elephants and avoid intruding into their comfort zones. In this instance, we were in the wrong place, the wrong time accidentally, and we were lucky to make a narrow escape. As much as a photograph is important, the images should be captured without risk to the subject or the photographer.”

Even Sleeping Animals Can Be Dangerous

It doesn’t matter if an animal is sedated. Sometimes going close to a sleepy one even can result in a scary moment, as Marsel Van Oosten found out one day. A widely published and awarded wildlife, nature and travel photographer, Marsel’s most frightening moment was when he had an opportunity to photograph a tiger really close up.

“When I was photographing wild tigers, one of the tigers was sedated with a dart to run some medical tests. I figured that would be a great opportunity to set up a remote-controlled camera with a wide-angle lens. The moment the tiger would wake up, I could get some wide, low angle shots. Immediately after the vet had given the antidote, I realized that I had placed the camera wrong, so I asked the vet if I could still move it. He said it would be fine, so I walked towards the tiger and picked up the camera.

At that point, it woke up, growled and jumped up, and started chasing me. I ran for my life, but luckily the tiger only managed to take a few steps as it was still groggy. No one was harmed, and that tigress later had a healthy litter of cubs.

The goal is always to prevent any kind of situation where the animal feels the need to charge you. When there is even the slightest chance your presence might trigger this response, you should always back off. But wearing a seatbelt is no guarantee you won’t get into accidents. I have been charged and chased by elephants, rhinos, hippos, lions, and arctic terns. Every time that happens, it’s unfortunate, but even if you try, you can’t always prevent it.“

It’s Not Always the Largest Creatures That Are the Scariest

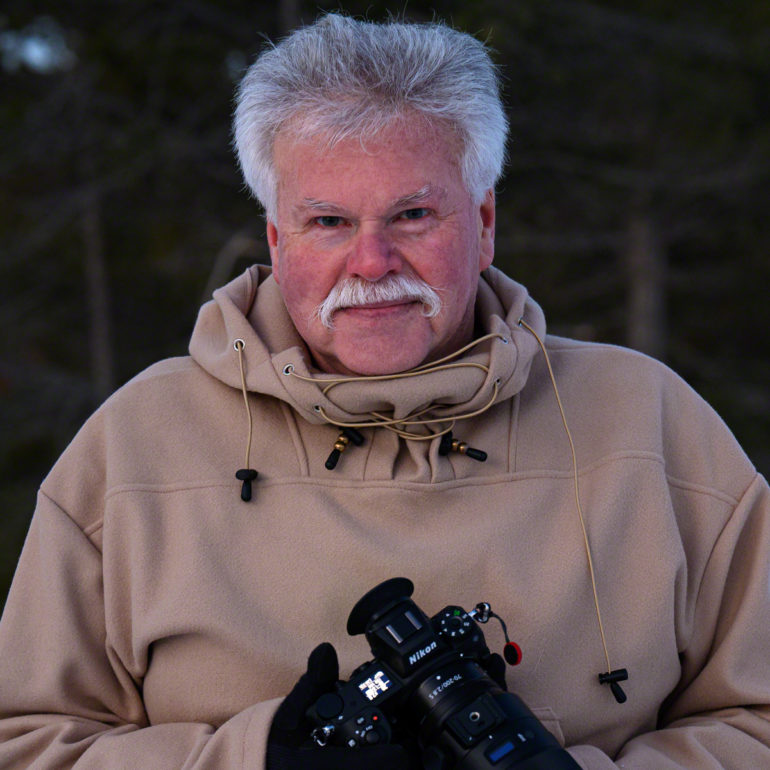

I’ve been following Moose Peterson’s stellar aviation photography for many years now. He’s also a very accomplished wildlife photographer, and I was thrilled to have him tell us about his most scary wildlife experience.

“It’s actually a common question that I guess goes with the profession,” says Moose. “With my photography philosophy that I have had from the beginning of understanding basic biology, it has permitted me to get the photographs I share without putting myself or my subjects at risk. I have not had a grizzly bear charge me or moose threaten me, never had an owl stoop on me or anything else give me fright in my forty years as a photographer.

The closest I’ve come to being scared was due to my own mistake of not drinking enough water. I was working in the desert of So. California photographing the endangered Delhi Sand Flower Loving Fly. The air temps were well north of one hundred degrees, and in photographing the male fly as they emerged, I didn’t stay hydrated. This led to me getting incredibly lightheaded and developing heat exhaustion. Luckily, someone I was with recognized it and sat me in the shade and poured water on and in me.”

“What has me scared, though, is to see so much of our wild heritage and its critters are in peril and disappearing. Since the 1970s, the planet has lost over half of its entire critter inhabitants. That’s 50% fewer birds, mammals, insects, the key members of what makes our world so special. This scares me! What scares me more is that places, locales where I went to photograph critters in the past are, in some cases, void of that wildlife now. We were very fortunate to have been left a very abundant wild heritage by past generations. The scary question is, do we have the foresight to leave a rich wild heritage to future generations?!”

Scary indeed, and Moose does raise a valid point about the future of wildlife. Most wildlife photographers these days also do their part in the promotion of conservation through their images.

Can Any Moment Be as Scary as Being Sized Up by a Large Animal?

Trai Anfield used to be a BBC natural history presenter for popular programs such as The Living World before switching to a career behind the lens. Since 2012, she has been running ethical photography safaris under a venture she set up, and she was actually on one of these in Uganda when I contacted her for this article. I knew she’d have a fantastically scary event to narrate, and she didn’t disappoint.

“Mountain gorilla trekking itself is not a scary experience – far from it – though this particular moment in Rwanda did make my heart beat a heck of a lot faster than usual!

It’s not every day that an enormous silverback comes to check you out and, in the words of my guide, “decides whether you are worth fighting or not.”

In reality, I think he was just making sure that the strangers approaching his family meant them no harm. It strikes me as miraculous and humbling that he gives us permission to join them, given the fact that historically humans have hunted, poached and just plain slaughtered mountain gorillas, so there are only 1063 left in the world today.

To be clear, on treks, we are not allowed to approach gorillas or go within 7m of them, but nobody tells Akarevuro, head of the Kwitonda family, the rules in his own home! So as we walked down this narrow trail, he barrelled down behind us. Our group parted to let him pass, and I squeezed as far back into the undergrowth as I could, but he stopped head to head with me.

Following the guide’s instructions, I knelt down to make myself small and unthreatening and also did not hold eye contact, which again can be interpreted as a challenge.

I had to stop shooting when he approached too; the camera was useless anyway when he came too close to focus. Instead, I had a GoPro strapped to my wrist and slowly and carefully switched the video on to record the encounter from my point of view. (Check out the video at the bottom of this article.)

He was so close I could smell his various scents and feel both his breath and his body heat as he eventually continued on his way. He inspired a primal respect and reverence that I’ve rarely felt, and although I didn’t feel threatened or fearful, I’d be lying if I said my fight or flight instinct didn’t thump in my chest, and I had to talk to myself to stay still, calm and get some shots! And thank you to Christina Gates for the image of the two of us together.

The next hour with his family was by far the best I’ve spent with gorillas; having checked us out, he relaxed, and the whole clan came out, and we felt welcomed rather than tolerated as we photographed mums with babies, naughty kids and the big guy himself. By the end of the hour, my heart rate had returned to normal.”

[ad_2]