Synopsis: As a hand-tool woodworker, Josh Klein loves the smoothness and workability of Eastern white pine, and he’s not keeping that news to himself. From the availability of wide pine boards to the ease of milling, light weight , and surprising durability, white pine has a lot to offer. And it’s not hard to finish, either, if you use some of Klein’s tips.

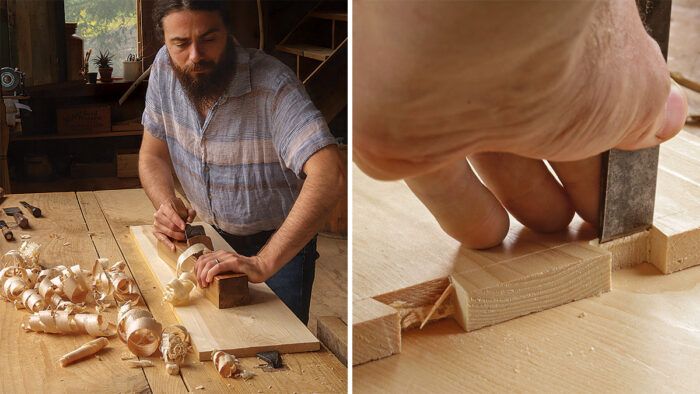

There is no wood I’d rather work than Eastern white pine. As a hand-tool woodworker, the ability to plane a chunky curl off a creamy smooth board gives me a sense of power that most folks don’t associate with working by hand. There is a reason that pine was used so extensively in historic furniture before the mechanization of the Industrial Revolution: It works like a dream. The good news for us is that these big trees, though massively diminished in the overharvesting and clear-cutting of the early colonists and the subsequent logging industry, are still around, and they’re still as workable, so pine remains an optimal choice for furniture, and also for enjoying yourself in the shop.

Wide boards are accessible and inexpensive

Who doesn’t love wide boards? Visiting historic houses or living-history museums, one of the most common remarks I overhear from other guests is how remarkable the wide boards are. It’s not uncommon to see boards 20 in. wide in historic homes and furniture. Especially when they’re prominently displayed in flooring or tabletops, we can’t help but wonder at the size of the tree they came from. But as hard as it is to believe, no one in the 1700s drooled at boards that wide. These boards were practical because they were local, abundant, easy to work, and inexpensive. Wide boards were barely more than the pre-industrial equivalent of plywood—economical, but not out to impress.

Since moderns like us relish the single-board glory of antiques, it’s noteworthy that to this day, wide pine remains relatively affordable and available.

Ease of construction

Craftspeople love wide boards for reasons other than their majesty and economy: Building with them is just so dang quick. When you have access to wide stock, edge jointing is rare. This task is so time-consuming in a hand-tool shop that traditionally craftspeople tried to use the widest stock they could find. And when they did join edges, they weren’t particularly fussy about it. Jointing added so much labor in planing square and straight, gluing, and planing flush, that it’s typical to find the underside/inside of the boards out of plane with each other and slathered in hardened glue squeeze-out. This no-nonsense approach is what furniture historian Myrna Kaye calls “economy of labor.” Only the show surface needed to look good.

Edge joints require surfacing, jointing the edges, gluing, and then resurfacing to flush the boards to each other. In contrast, if you have a wide enough board, you can build a chest out of it without any edge jointing. Think about the time savings on a small tabletop made of one board: Just plane it and cut it to size. Large dining tables can be two boards—only one joint. And the labor-saving benefit of wide stock also applies for those who use machines. However you work your wood, if you’ve ever spent time edge-jointing and gluing up 8-in.-wide boards to make a top, try a single-board top sometime. It feels like cheating.

What milling you do need to do is much easier on pine than hardwoods. Probably 75% of my planing is done with a heavily set jack plane. With this tool, I can take numerous deep bites without fatigue. When I work in hardwood, however, I have to take about half as much material per stroke. This difference adds up considerably by the end of the project. Sawing is faster, too.

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below.

|

Confessions of a Hand-Tool Woodworker |

|

Give pine a chance |

|

Pine(ing) for perfection |

Download FREE PDF