[ad_1]

![]()

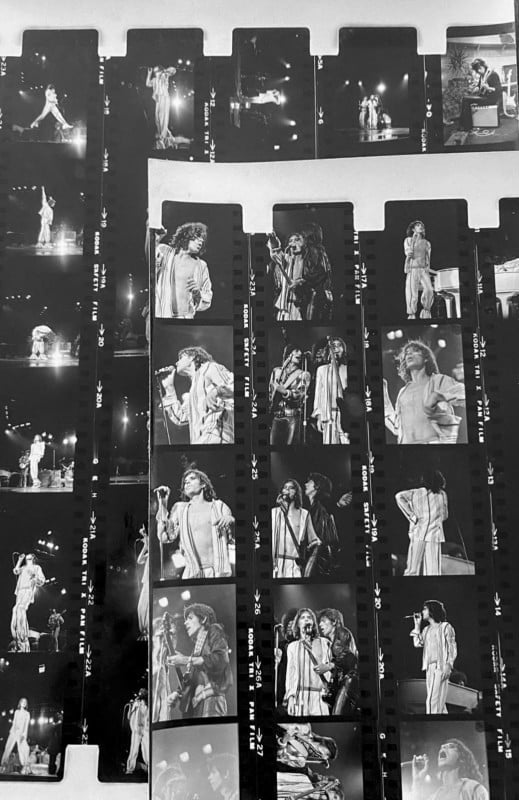

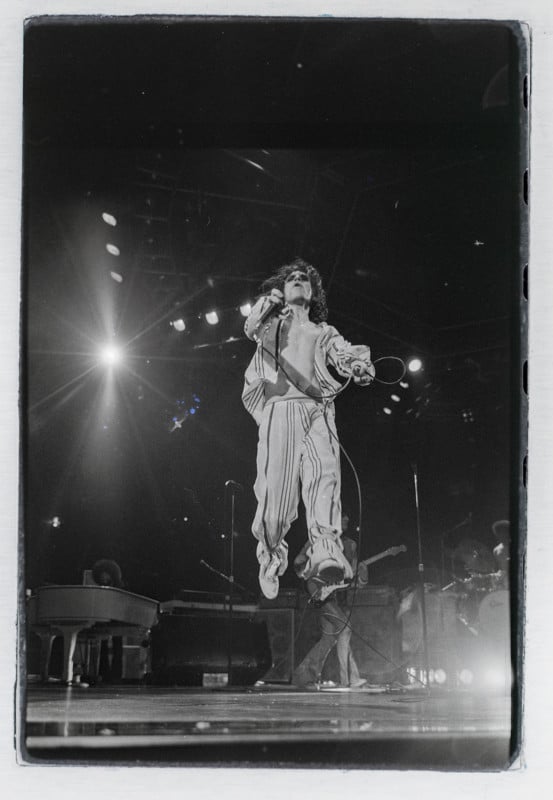

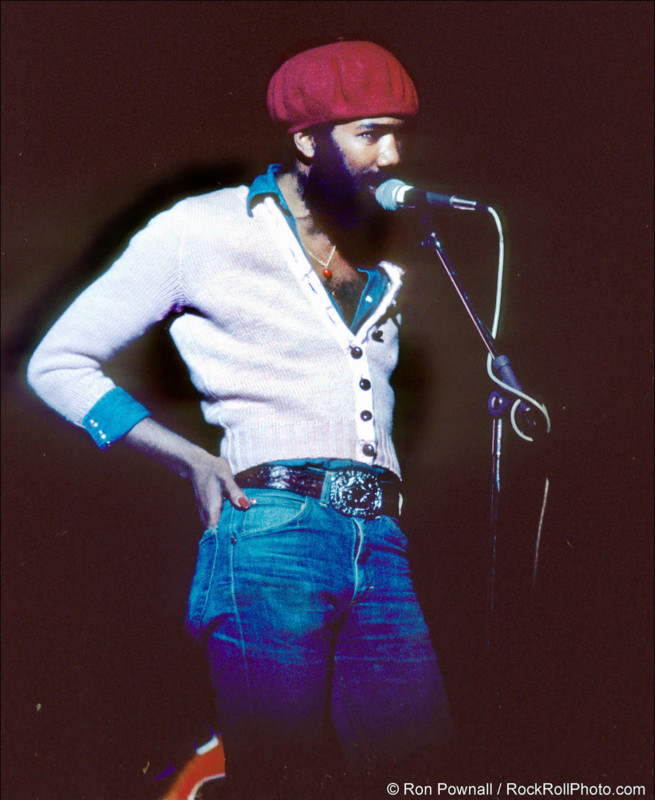

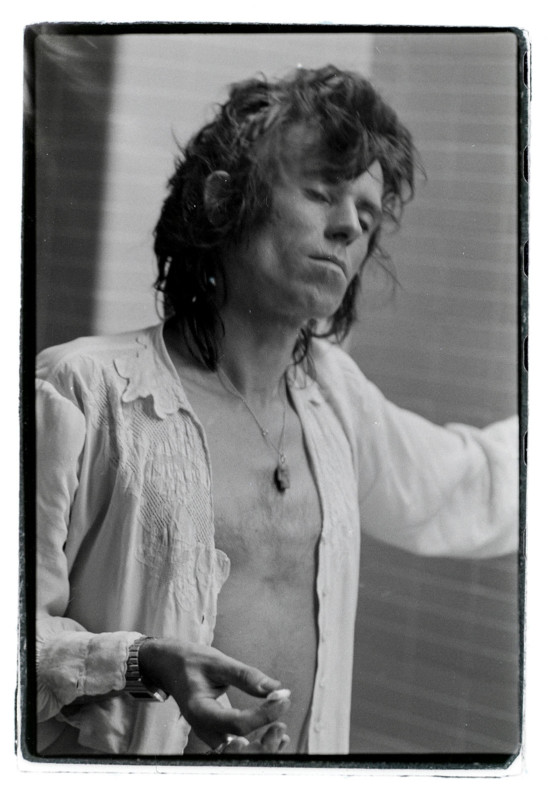

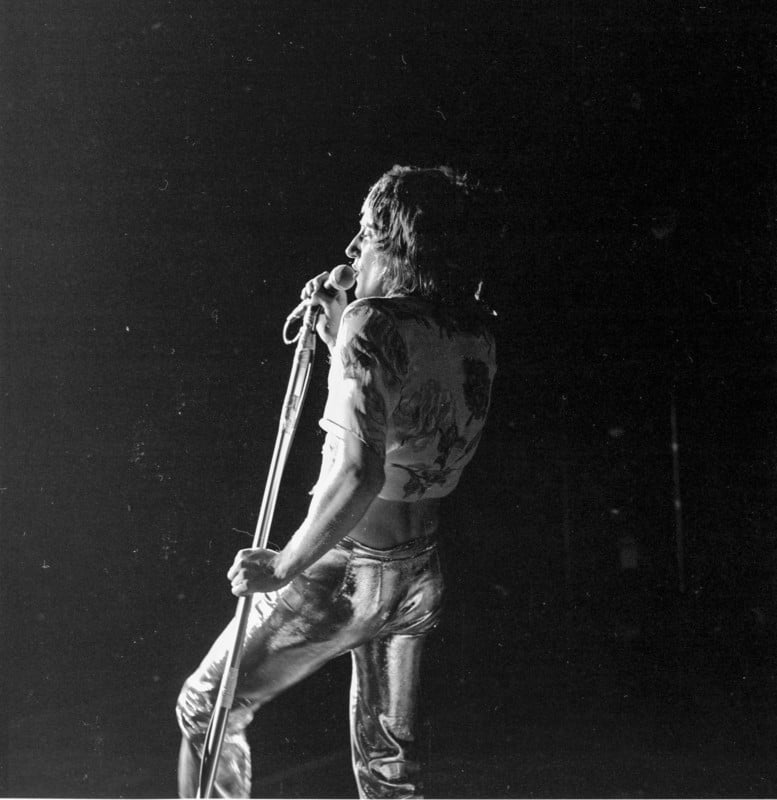

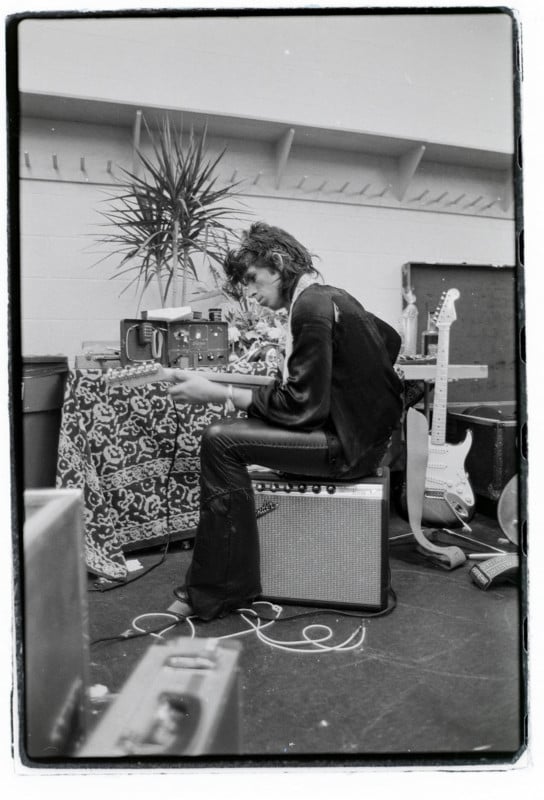

Photographer Charles Daniels has been photographing famous rockers like Rod Stewart, Jimi Hendrix, The Who’s Pete Townshend, Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler, and others since the late 1960s. However, tens of thousands of his photos have never been seen — they are sitting in roughly 3,200 rolls of undeveloped film in his Boston home.

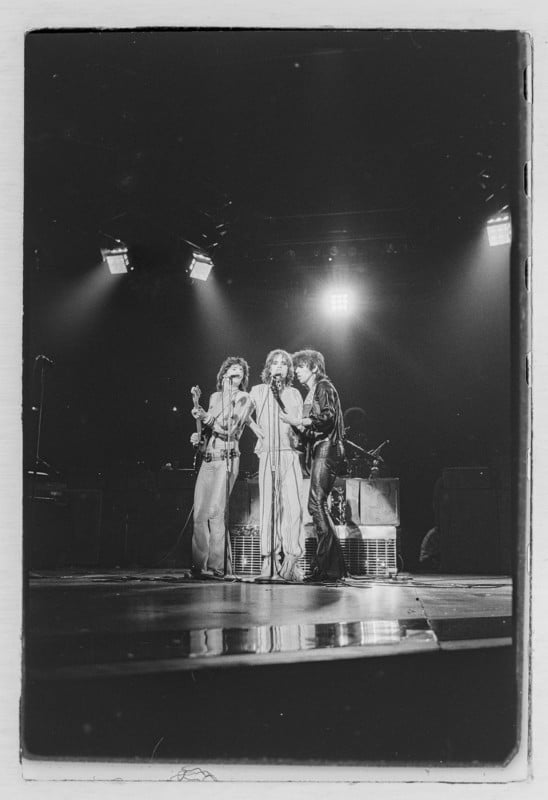

Much of Daniels’s work was shot at the famous Boston Tea Party, a concert venue in Boston, Massachusetts, that hosted famous bands like the Grateful Dead, Chicago, Neil Young, Frank Zappa, Pink Floyd, Fleetwood Mac, The Allman Brothers Band, Joe Cocker, Led Zeppelin, The Who, Sly and the Family Stone, and more.

“The Tea Party was open from 1967-1970 in two locations,” Daniels tells PetaPixel. “I was the only emcee.”

A Prolific Rock Photographer

The Master Blaster, as the club’s flamboyant emcee was known, kept his camera handy as he schmoozed with the celebrity musicians. Daniels was able to capture countless unguarded moments as Led Zeppelin, The Who, Faces, and others launched their careers at this very venue.

“He was a great guy… he was somebody that everybody liked,” says Ray Riepen, who started the Tea Party in 1967.

Photographer Lou Jones, who has been working in Boston since 1970, describes Daniels as “very approachable…everybody wanted to be the Master Blaster.”

Musician Peter Wolf, who used to host a midnight slot as a DJ on WBCN, was the one who originally dubbed Daniels the Master Blaster. But it was more than a nickname — it was a persona. Daniels says that he knew hundreds, maybe thousands of people who called him that but had no idea what his actual name was.

Daniels enjoyed the act of shooting but never spent time on developing (pun intended) his photography. Most of the exposed rolls just went onto be collected in some garbage bag, although the photographer kept the important ones in Ziploc bags or at the bottom of his fridge in his house in Somerville, Boston.

After the Boston Tea Party closed due to the escalating cost of booking bands that started playing large outdoor festivals, Daniels started working at other venues where he also kept on shooting.

“There was one night when I was running between the Music Hall [now the Boch Center’s Wang Theatre] and the Orpheum [Theatre], announcing bands in both places,” Daniels recalls. “I don’t know if you know Boston at all, but it was actually quicker to run between the two than to try and drive.

“Bands at the Tea Party often played there Saturday night then would play on the Cambridge Common for free on Sunday afternoon. It’s hard to explain now since it has been completely gentrified, but back then, Harvard Square [in Cambridge, Massachusetts] was the center of the counterculture scene.”

All of Daniels’ imagery was either candid or live on stage. He never posed subjects and he never used a flash.

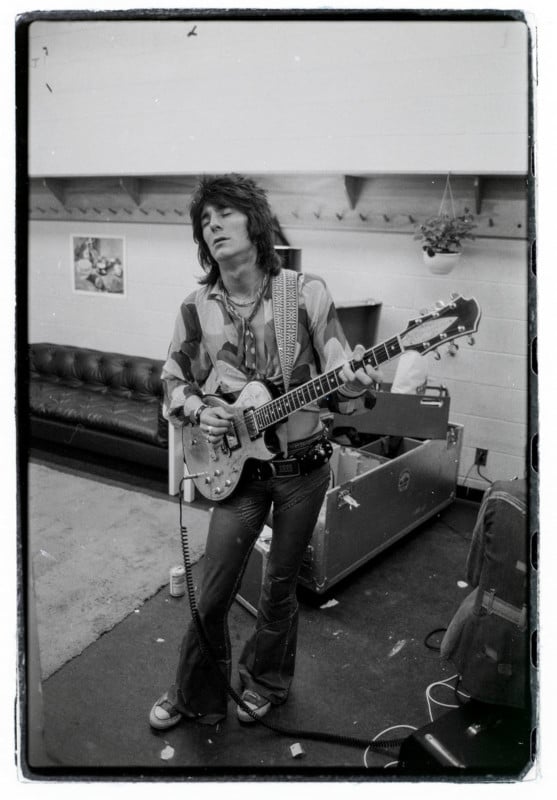

In 1975, Daniels joined guitarist Ron Wood during his first tour with the Rolling Stones. The band’s tour photographer at the time was the now-legendary portrait photographer Annie Leibovitz.

“Annie was the official tour photographer, and she wasn’t thrilled that I was allowed pretty much-unlimited access with my camera,” says the Master Blaster.

The Start of a Massive Undertaking

Daniels’s massive collection of undeveloped film was hidden away from the world for decades, but a push to process the unseen historical photos has gained momentum over the past couple of years thanks to social media.

“It’s kind of a COVID story,” explains the Master Blaster. “Our local arts council, the Somerville Arts Council, offered a series of small seed grants to help artists back in 2020. We used the money to develop about 100 rolls at a local Boston Lab, Colortek, which I have been using for years.

“I’m not on social media at all, but my partner [the artist Susan Berstler who founded Nave Art Gallery] started posting a few images that turned up on Facebook. I should probably admit that I didn’t always label the canisters after I shot a roll.

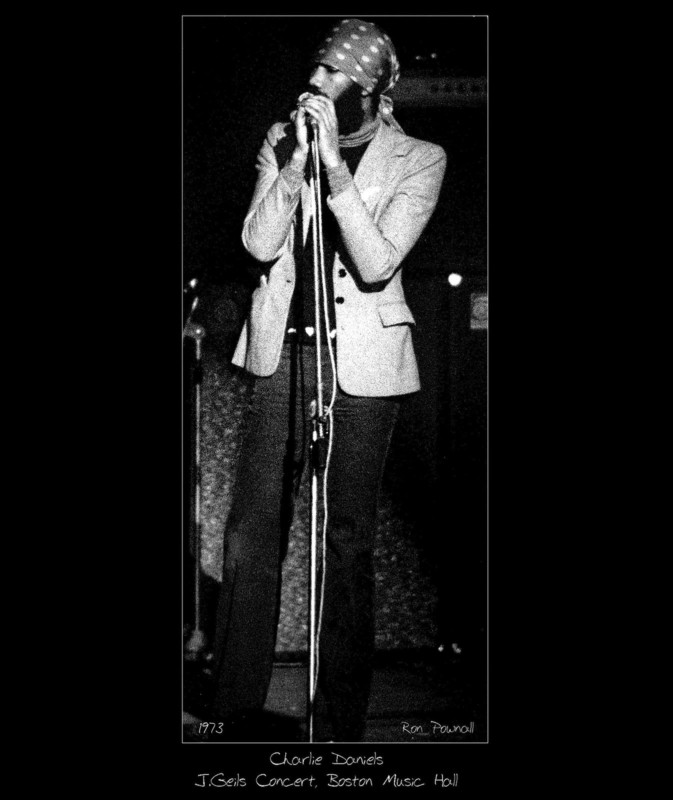

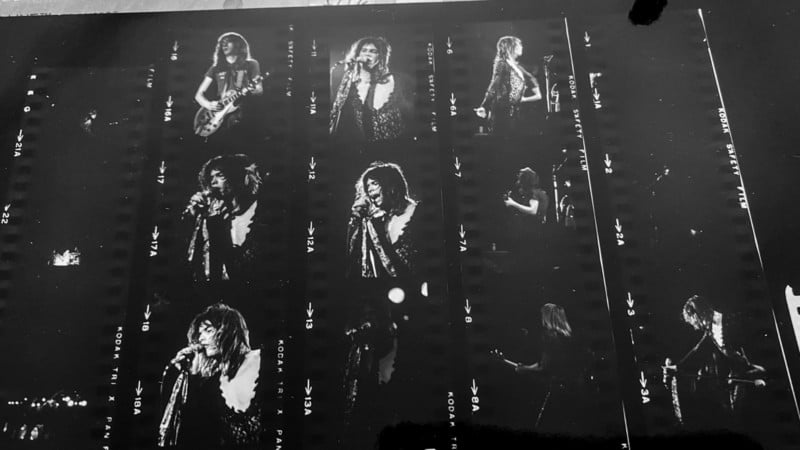

“She was mostly posting the music images — I think we found some Frank Zappa, J Geils, and Faces on tour in that first batch. The response to those pics convinced us that we were sitting on something special.

“When we realized how much truly old and difficult to develop film we had, Susan started looking for a lab that specialized in that and we found Film Rescue.”

Berstler reached out to Film Rescue International, a company that first started developing expired films in 1983.

“Her first email was simply asking if we offer any kind of volume discount for large orders,” partner Greg Miller, whose official title at the company is Commissioner, tells PetaPixel. “As a policy, we, for the most part, don’t discount, which I let her know, but once we saw what she had, we knew it was a project we wanted to be more intimately involved with. Since then, we’ve been working with her to get this work done and also to try to get Charles’ story told.

“We regularly get in film from the 1920s, which we can pull images from, but it’s hard to pinpoint the actual date of a lot of these films. We often have to go by the fashion and cars we see in the pictures.

“More often than not, we don’t have the box with the expiry date. We try to keep records of what packaging was from what year, but it’s a huge job.”

The oldest film that Miller has developed is a Kodak film that expired in 1908, but that was one that he exposed himself. It was a test film he bought from eBay, which would have most likely been the same kind as the film in Mallory’s [English mountaineer who disappeared on Mount Everest in 1924] camera that National Geographic had sent a crew up Everest to find. The company was on deck to process that film, but the film and camera were never [even to this day] found.

It remains to be seen whether Daniels’s film was preserved well and whether high-quality photos emerge from the decades-old film, but early results have been promising.

“For years, I considered myself a B&W shooter, but there is a fair amount of color and slide film as well,” says Daniels. “It’s about two-thirds 35mm and the rest 120. The largest amount of any single film is by far [Kodak] Tri-X.

“There’s a stash of Kodachrome as well as E4 [slide film, that was introduced in 1966], which I am curious to see how the Film Rescue lab handles. We have done some test rolls with good results of the Kodachrome. There’s probably more Kodak than anything else but also Ilford and Agfa as well as a few other brands.”

The Photographer and His Cameras

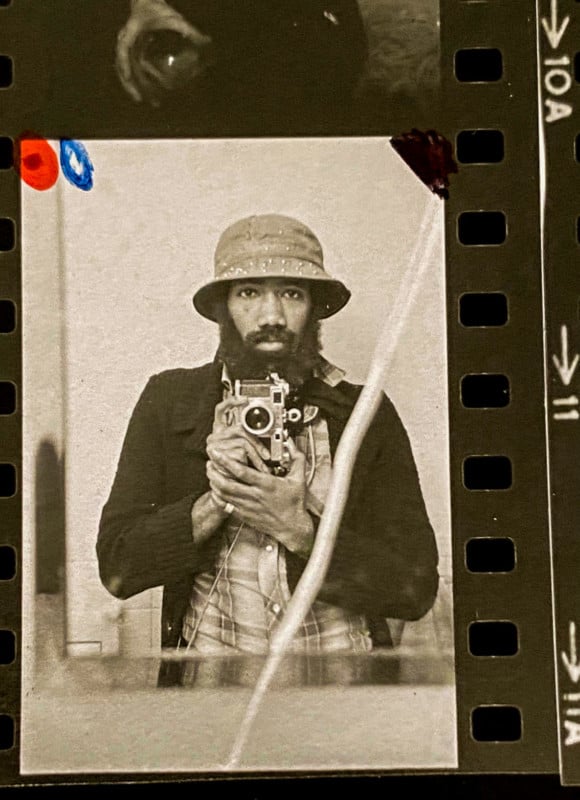

“I’ve always been a Nikon person,” reminisces Daniels. “Folks used to call me Two Nikon Charlie back in the day. The Nikon F3 is a classic, but I also use a Nikon F5. To me, the F5 is pretty much the ultimate film camera, although my girlfriend claims it is too heavy.

“Some of the older music images were probably shot with my first Nikon, the FTN [a late model Nikon F body combined with the Photomic FTN metered prism.] My favorite Nikkor lenses are the 85mm f/1.4, 50mm f/1.4, and 35mm f/1.4. And maybe the 105mm f/2.5.

Editor’s note: Daniels later corrected himself to say the early music was shot with a rangefinder, so either one of the Leicas (M2 or M3) or the Nikon SP.

“That said, I also loved the Leica M3 — my favorite lens for it is the 35mm f/1.4. That was pretty much the perfect documentary setup. My M3 was painted crazy colors by a friend – people would never do that today, but that was a time of hippies and not a lot of rules.

“For medium format, I still have and use a Hasselblad 501CM. And I have a Mamiya 6. I shoot a lot of street stuff, and rangefinders obviously support that. I have a Rolleiflex 2.8 F – it’s a wonderful camera.

“Oh, and after a trip to Prague [the capital of the Czech Republic] in the 90s, I came home with three Pentacon Six and the most amazing fisheye lens. The bodies are known to be problematic, so the shop sold me a couple of spares for parts.”

Daniels still holds onto most of his cameras and even today “use[s] many of them.” He even had a darkroom in his house, but “it wasn’t a very good setup.”

Berstler says that Daniels could be found with a light meter around his neck in many of the early photos she has seen of Daniels.

“He’s always been a gear guy — maybe that’s why his film piled up as much as it did,” surmises Berstler. “When he had the money, he was likely to buy another camera or lens. I do know he had a Hasselblad as well when he was touring with the Faces.”

From Segregated Alabama to Massachusetts

Daniels grew up in Luverne, Alabama, 100 miles south of the capital Montgomery, on his grandparents’ farm.

“Well, it was a very different world than Boston, that’s for sure,” says Daniels. “I remember bringing water out to my relatives who were working in the fields, picking cotton. I was like 5, 6, 7. You always had to watch out for snakes. I was convinced there was one snake that was hiding, waiting to scare me.

“But the South was a very segregated place then — in every way from water fountains to churches. It’s hard to describe how different things were. My grandfather would put chairs in the back of a wagon and hitch up the mules to take everyone to church on Sunday.”

When Daniels was around 11, his family moved to Roxbury, Massachusetts, a little south of Boston.

He found a Brownie Hawkeye in his parents’ closet and started taking photos of his neighborhood. Daniels enjoyed street photography, taught himself the ropes, and the photographer in him was born. He ventured out further from home in the next few years and regularly photographed at Harvard Square.

Fast forward five decades and Daniels is now dealing with health issues as he eagerly looks forward to seeing what becomes of his photo archive.

“I was diagnosed with Myelodysplastic syndrome around Thanksgiving and started chemo on my birthday, November 30,” says Daniels. “I am in the middle of that cycle now.”

Raising Funds to Process the Film

“I am excited about the response he has been getting,” says Berstler. “His work, his photography, and the undeveloped rolls obviously mean a lot to both of us, but it was a surprise to see how other people have responded to his story.

“We have had over 400 donations made to the project’s GoFundMe, which has been humbling. We are both so grateful to everyone for the money to continue developing the film.”

Daniels wants his followers to know that this is an expansive collection of films shot over the past 50 years — not just music from the 60s/70s, although that has garnered the most interest. Daniels’ art has grown since the Tea Party days, expanding from fashion and music to dance, performance, protests, street, and everything in between.

“Charles used his camera almost like a sketchpad, documenting his day,” Malcolm Gay, arts writer at The Boston Globe, tells PetaPixel. “What you get is a chronicle of the era, everything from street scenes to unguarded shots of musicians who later became the biggest names in rock & roll.

“Everyone I spoke with said the same thing: Charles had an insider’s perspective; they can’t wait to see what’s in the time capsule.”

The GoFundMe crowdfunding campaign to raise money for developing and digitizing Daniels’s photos has raised over $34,000 of its $40,000 goal at the time of this writing. Assuming the effort does get funded, the world may soon be treated to tens of thousands of new never-before-seen photos that add to the history of rock ‘n’ roll’s most famous figures.

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at The International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him here.

Image credits: Header photo of Charles Daniels with his undeveloped film rolls by Susan Berstler. All photos of musicians by Charles Daniels. Self-portrait by Charles Daniels.

[ad_2]