[ad_1]

![]()

My name is Virgil Reglioni, and I am a 33-year-old photographer from France. I have spent the last six winters working as an outdoor nature guide and aurora photographer in the Arctic.

After discovering Lapland, Finland, for the first time in 2016, I witnessed my first northern lights (aurora borealis) and got hooked with night photography and especially the auroras.

This unique niche of photography has now become my signature genre as a photographer.

I simply adore exploring and finding new places hard to access in deep valleys or mountain tops. I aim to catch the “never seen before” aurora photographs. To me, this is a key aspect in my photography–the unseen. I want to capture the northern lights in a way we never see it, to be able to enhance its uniqueness and spontaneity.

Throughout my evolution into photography, I have been focusing on building impactful aurora photographs that gather organization, plan-making, and deep creativity. It has now become my strength.

To me, fine art aurora photography is one of the most complex styles of landscape and night photography because it brings together a vast amount of knowledge about the aurora, the weather, the locations, and of course technical photography. It requires plenty of patience, creativity, frustration, and perseverance.

Some of my photography work takes a huge amount of time and many attempts before capturing the right moment–sometimes spread across a few winters. This is why I wish to share the stories behind the photos I take. In this article, I will tell the story of how and why I captured some of my most unique and epic aurora photos.

An Entertaining Preparation Process

The preparation of our project was such an entertaining process. We had studied this place for a long time and we got this idea a year and a half ago. Florian Ledoux, my best friend here in Tromsø, had spent many ski tours up on this mountain top located on the Western side of Tromsø city.

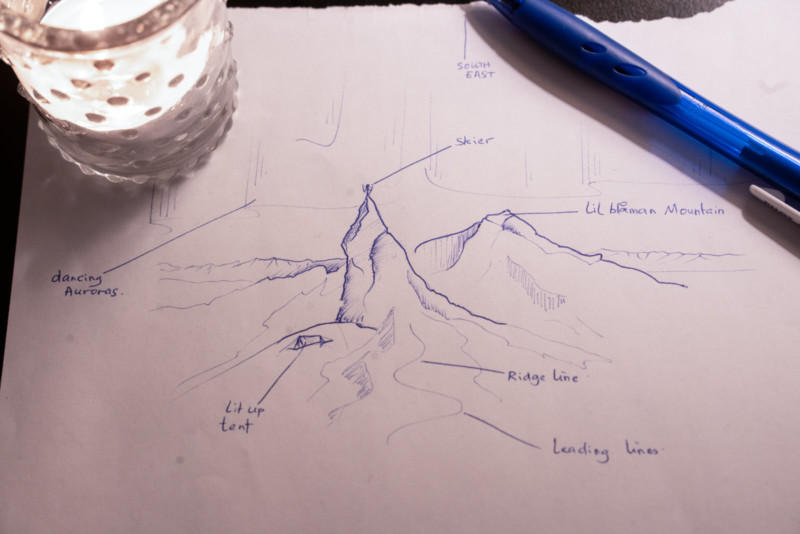

Florian kept on showing me some really nice phone photos of the impressive mountain formation, which gave me this insane idea: why don’t we try to get you up there, standing on the top of this tooth, with some dancing aurora behind you, Tromsø city lights in the back, and our tent lit up on the side? It sounded like a dream shot to me, but not the easiest to plan and achieve.

It did not take long for both of us to agree that it could be one of the best projects of the winter.

The Photo Would Require a Lot of Gear

The project got stuck in our mind and we started to plan. With about 25 kilograms (~55lbs) of equipment on our back, we had to gather quite a lot of equipment such as avalanche safety gear/probe, shovel, beacon searching device, and also our camera equipment, including our tripod and strong headlights. We knew the wait up on top of the mountain could be long, so we decided to each bring a -30° sleeping bag and a tent so we could shelter in case of bad weather and gather some heat.

Spare clothing was mandatory as we would reach the top wet with sweat after skiing up 750 meters in elevation.

We also knew that communication could be an issue because I would be staying at the bottom of the tooth, and he would be standing up there, exposed to the wind. To help in this process, we took with us some VHF radios to be able to speak to each other correctly.

Aurora Intensity Need to be On Point

To be able to capture the aurora correctly, we had to understand what direction we were facing to be able to calculate what intensity of Northern lights we needed.

When we know what aurora index we need, we know what night we could go. After studying the exact spot where I wanted to take the photo from, I figured out that I would be facing toward east or southeast. That brought us to the conclusion that we would need a KP index of 3/4 out of 9.

Once this is decided, we would keep a constant eye open on the aurora previsions during the upcoming weeks, so we could plan the night and decide when we want to lunch the mission. We would also need to time it perfectly with the weather forecast, my time off work, and Florian being free to join the mission.

Hope for an Accurate Weather Forecast

We needed to have a completely clear sky to be able to see the lights, as if clouds roll in, they would cover the sky and prevent us from seeing them. By saying completely clear, we literally mean 100% clear so we could avoid any light pollution from the city bouncing against the clouds.

We wanted to avoid wind because staying in the cold under 20 degrees below zero for 4 or 5 hours can be really exhausting and could be amplified when the wind gets stronger. By standing on top of the tooth, my little skier puts himself in a tricky position which is not really safe when the wind is strong.

It’s All About the Timing

We wanted to minimize the time spent up there because under really cold conditions, standing still for a few hours can be tough, tiring, and boring. When facing some hard conditions and for a long stretch of time, our productivity and efficiency decrease heavily. This can be prevented either by finding warmth or by reducing the time spent out of the comfort zone. While we were hiking up, my fear was that the aurora would already be active on our way up.

We did not want to rush the moment and feel we were missing out on the aurora activity. On the other hand, we had to plan some spare time when we would arrive. We wanted to be able to scout, understand where to set the tent for the great placement on the photo, but also have time to gather all the right elements to build a powerful composition. All of this before the northern lights fill the sky.

The First Attempt at the Photo

Our first attempt was on February 2nd, 2022, and the forecasts were looking amazing. Everything was lining up for us, clear sky, soft wind expected, strong aurora with KP6 predicted, and really cold temperatures. It was forecasted to be -17° Celsius (1.4°F) and a feel-like temperature of -24° Celsius (-11.2°F).

After gathering all the equipment we would need during the afternoon, we started the hike at about 18:30. We reached the top at around 20:00 in search of all the elements we needed, thoroughly planned earlier. The clear sky was here as predicted when we arrived.

We spent an hour scouting when we reached the top, trying to understand where to place the tent, where to stand with my tripod, and how to find the right composition. Meanwhile, Florian went scouting to find a route that could lead him to the top of the tooth.

This is when we encountered our first issue: there was a layer of thin snow covering a hard icy layer, making the way up really hard and slippery without crampons or an ice ax.

After 4.5 hours of waiting, sheltered in the tents, the wind picked up heavily, sending snowdrift on top of our gear and our tent. It forced us to pack quickly, move away from our spot and reach the bottom of the mountain under really bad snow conditions.

The weather forecast appeared to be quite wrong as there were way more clouds than expected. Also, the wind picked up at around 13 or 15 meters per second around 1 o’clock in the morning, making it really uncomfortable to capture images or even to pack our equipment with a lot of snowdrifts.

A Failed Attempt, But Lessons Learned

This first attempt did not succeed, but we learned some really important outcomes from it. We realized that we would need to bring ice axes and crampons for the next attempt as the ice conditions change pretty fast.

Overall, it was a great success in terms of the information we gathered. We felt ready and more knowledgeable for the next time. I did find the composition I wanted, I understood the settings I would need, and we knew how to safely access the top of the tooth. We also figured out its exact orientation and most importantly, where to place the tent and try to leave no footprints to keep the snow clean of tracks for a neat photo.

After this first attempt, I learned a lot about the camera settings I needed. It all became more organized in my head.

I had to take into consideration the light pollution for Tromsø, which would affect a lot of the settings. My idea was to take a few times the same photos on different expositions to get the city light well exposed, but also have it as a panorama.

One thing was really important to me: I want to capture these shots within a few seconds apart because I wanted to grab a full homogeneity into the frame.

An Evolution of the Composition

Florian Ledoux was going to be my subject in the photo, a skier standing on top of this impressive tooth. The plan was to build a really constructive composition with the main mountain shape in the middle. By placing our tent lit up on the left side, we show the proper context of the night.

I wanted to create a panorama of two wide-angle shots, but the skier on the photo would barely be visible because the lenses were too wide. Having Florian standing on the top of the tooth would not allow me to have his full body. I was not able to capture his legs. The outcome would probably only be a headlight visible. This is not what I wanted.

I decided to place him on the right side of the frame to create more balance, such as a triangle into the photo with the tent on the left, the tooth in the middle, and the skier on the right.

The Second and Final Attempt

The second and final attempt was on February 21st, 2022. On that evening, all the stars lined up to offer us the best rewarding night we could wish for. It took us about 1.5 hours to ski up the mountain and start setting up our tent. The aurora was not visible yet which gave us time to analyze our surroundings, the different snow conditions, and the right orientation.

We spent a total of 6.5 hours outside this night, with a crazy temperature of -27° Celsius (-16.6°F) felt on top of the mountain. We did shelter in the tent to get some hot food and stay as warm as possible.

Throughout the night, the cold was really affecting my photography, as I was all the time switching lenses. I wanted a panel of wide-angle shots, but also some close-up ones. I kept on changing my focal according to the aurora movement in the sky. I believe I did this process maybe 17 or 18 times during the evening, losing feeling in my fingers every single time.

Unfortunately, I gathered some unwanted scratches on both of my lenses this night. Luckily it did not affect my final photographs. The cold was sharp and I remember some moments when I could not even press the shutter to capture the image because I had absolutely no feeling of my fingertips in both hands.

When standing on top of the tooth, Florian also launched his drone in the air to be able to capture the full perspective of the landscape around us. It gave us an amazing magnitude of the place.

Thanks to this aerial view, we can see the setup and the work we put on to grab these precious images. Florian is on top of the tooth, the tent is on the left side, and I am on the snowy ridgeline below, figuring out my camera settings.

![]()

Having a photo where Florian is on the top of the tooth was probably one of the most important things, and I managed to gather this image around 10 PM. In this photograph, we can see the full oval of light from North West to North East, and Florian standing on top of the tooth on the right side, with his headlight on.

This series of images is one of my best works with aurora. Shooting such images in these conditions brings an incredible feeling of satisfaction, especially after spending such a long time building hope and excitement to grab that unique aurora shot.

The first few photos were taken with the auroras dancing in the North. I gathered at this moment some of the most impressive panorama photos ever taken with the aurora. We were patiently waiting for the green lights to appear in the South East, to be able to see them dancing behind the tooth.

The Final Shot Finally Happens

At 23:30, we started to see the northern lights slowly crossing above our heads, and gently gathering above the tooth, facing southeast.

We could not believe it. We were thinking at this moment: “There we go, it is happening!” The excitement was really high. It took me 5 seconds to put the battery of my camera back into its socket, and click to grab the shot.

![]()

I wanted to document the whole project to be able to inspire with my photography. This is about sharing my passion and my love for the Arctic. I want to show what it takes to capture the real aurora, the one that appeared at this exact moment in time. These are hours of work behind the shot, a lot of effort and frustration, by trying over and over.

Many people who see my work call me “lucky” on social media when they see what I capture, but they don’t try to understand the work behind my photographs. Many people who follow my work more closely then understand how much effort, passion, and love I put into planning a powerful photo I have in mind.

This is what creates powerful and meaningful images.

As I always say, “A good photo of an aurora is a good photo even without the aurora.”

About the author: Virgil Reglioni is an award-winning landscape and night photographer based in Norway. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can find more of Reglioni’s work on his website and Instagram.

[ad_2]