[ad_1]

![]()

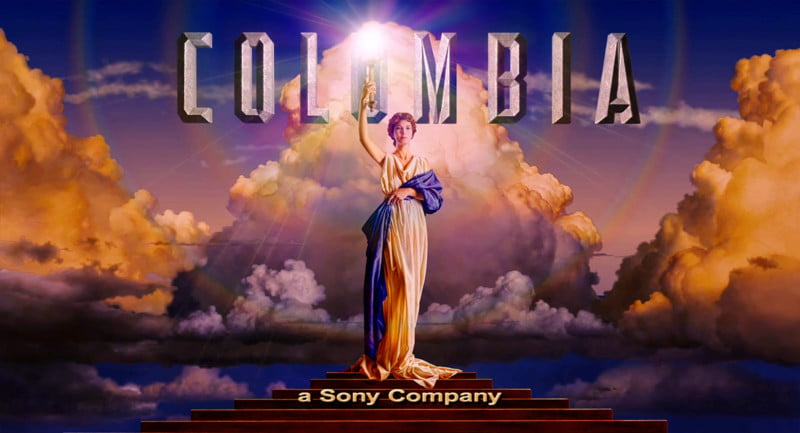

The iconic logo of the lady holding the torch that you currently see at the beginning of every Columbia Pictures movie was born in the apartment of Pulitzer Prize-winning New Orleans photographer Kathy Anderson in 1991.

The final version is a painting, but few people know that it was based on a photo of the photographer’s colleague, captured during a portrait shoot in a small space using very simple props.

The Story Behind the Photo Shoot

It all started when Anderson’s friend, the talented illustrator Michael J. Deas, who has designed 16 commemorative stamps for the US Postal Service, asked the photographer to shoot a reference photo for a painting. At the time, she had no idea how iconic the artwork would eventually become.

“Michael had a vision for the piece,” Anderson tells PetaPixel. “I created a soft light that would accentuate every fold in the material and flatter the model.

“My penchant for the large softbox light modifiers [a Chimera softbox on Dynalite strobes] proved perfect for the assignment.”

At the time, Anderson worked at the New Orleans newspaper The Times-Picayune. Deas needed a model to pose for the torch lady, and he decided to ask the photographer’s coworker at the paper, Jenny Joseph, to model.

On the day of the shoot, Deas arrived with a box of warm croissants from his favorite French Quarter baker as well as an assortment of props that he had visualized would work well for the reference image. There were sheets, fabric, a flag, and a small lamp with a light bulb sticking out of the top — a lamp that vaguely resembled a torch.

An Apartment Studio with Simple Props

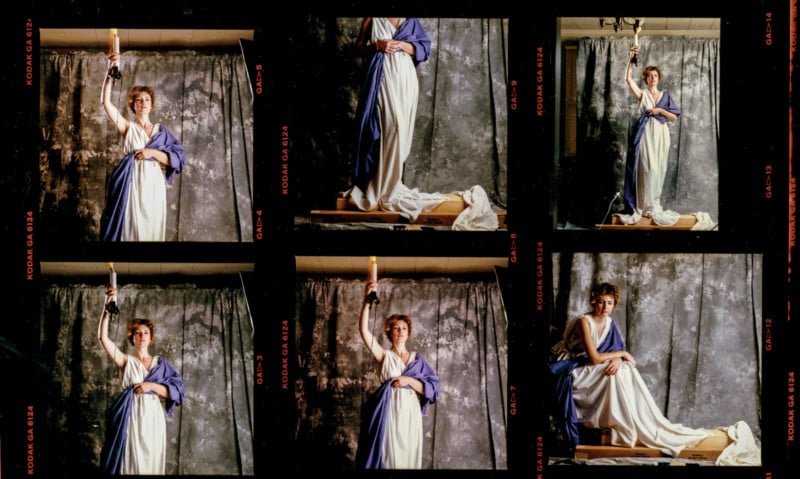

“After moving my dining room table out of the way and converting the living room into a studio, I set up a mottled gray backdrop. I placed a couple of boxes on the floor to let the fabric drape. I put a Polaroid back on the Hasselblad camera to start with some test shots.”

In the old days of film, a kind of early “chimping” was still prevalent, especially on 120 film shoots. Many Hasselblad shooters, including Anderson, would knock off Polaroids to see or show the client 21/4x21/4 proofs.

Several Polaroids were shot during the “torch lady” photo shoot, and the bedsheet also had to be readjusted around Joseph, who has never modeled again since that day.

“Jenny was wrapped in a white sheet,” Anderson recalls. “We shot with the flag draped over the sheet and some with the blue fabric draped over the sheet. Ultimately, we chose the blue fabric.

“The materials were carefully arranged. Lights were placed to accentuate folds in the fabric and create a catchlight in the eyes of Jenny. We began a fun-filled and creatively fused couple of hours of shooting, studying.”

“During the shoot, Jenny asked if she could sit down for a minute,” says the photographer. “I shot one frame of her seated, which may be my favorite image from the shoot. But after chatting for a minute, she confided that she was pregnant. After congratulating her, we resumed shooting, but I was worried about her standing on the box.”

The ‘Torch Lady’ Portrait That Became an Iconic Logo

Anderson was delighted with the images she produced that day. The photographer has shot many reference photos for Deas over the years, including book covers and commissioned portraits. However, none have equaled the movie logo’s fame.

Comparing the original photo by Anderson to the finished logo artwork by Deas, one can see how closely the artist stayed true to the original portrait. Details such as the arrangement of the fingers of her right hand as she grasps the lamp/torch, the blue cloth a little lower down the lady’s shoulder, and the fabric as it spills over the boxes/steps at the bottom are very much like the camera image.

![]()

“Even if the ‘Torch Lady’ painting had not become famous, the photo shoot would hold a special place in my heart, maybe because it took place in my living room, with my good friends, and with those perfect croissants,” Anderson says. “I will always remember this day fondly.”

A Long and Successful Career in Photography

Anderson first picked up a camera in college and has never looked back. She says she is happy to have been a part of the glory days of print journalism when she was a staff photographer at The Times-Picayune newspaper for 28 years. In 2006, her coverage of Hurricane Katrina was included in the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service for the newspaper.

Anderson is still an active photographer dividing her time with commercial work, portraits, a few weddings, and a decades-long personal project about the culture of New Orleans.

When asked which image is the most challenging photo she has ever shot, her answer is a photo she made inside St. Paul’s church shortly after Hurricane Katrina.

“That is because this was part of my children’s school, and I spent every morning in the chapel with the students,” the photographer says.

And the “most surprising use of a news photo” Anderson has ever made? An image of a state representative being held in a chokehold by a police officer during a protest about a racist monument. The 1993 picture was part of a year-long project about race relations in New Orleans. In 2016, 23 years later, the image was made into a poster and held high during the Black Lives Matter march.

Anderson hopes people feel something when they look at her work, whether sadness (Hurricane Katrina) or smiles (Columbia Pictures logo).

“If they engage emotionally, I have succeeded,” she says.

You can see more of Anderson’s work on her website and Instagram.

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at The International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him here.

Image credits: All photographs by Kathy Anderson. Columbia Pictures logo illustration by Michael J. Deas.

[ad_2]